Why is everyone using anti-Asian slurs?

Content warning: This blog post contains real-life examples of highly offensive language, including uncensored racial slurs. These terms are presented explicitly to ensure clarity for readers who may not be familiar with them. Our intent is to expose and educate, not to normalize or condone their use.

Pop culture isn’t part of our regular news diet, but during the last few months, two headlines caught our attention.

First, on Love Island USA, contestant Cierra Ortega was removed from the show after it was revealed she had used the anti-Asian slur “chink” on social media — twice.

Days later, Oasis frontman Liam Gallagher used another anti-Asian slur —“ching chong” — in a post on X, ahead of the band’s reunion tour.

At a time when anti-Asian hate remains prominent, it’s not surprising that anti-Asian slurs remain embedded in our public discourse. What did surprise us, however, is what happened next.

In response to widespread backlash, Cierra issued a statement claiming she didn’t know that “chink” has racist implications. And after deleting his racist tweet, Gallagher mocked the controversy onstage, at one point asking the audience — “You’re allowed to say ‘grasshopper,’ right?”

For the record, both “chink” and “ching chong” are racist slurs. In fact, they are some of the most common anti-Asian slurs out there, according to recent analysis. But since there seems to be some confusion, we’re dedicating this edition of Keeping Count to defining — and breaking down — common anti-Asian slurs.

Keep reading for more on where they come from, how they are used, and what they can tell us about the current state of anti-Asian racism and xenophobia.

By the Numbers

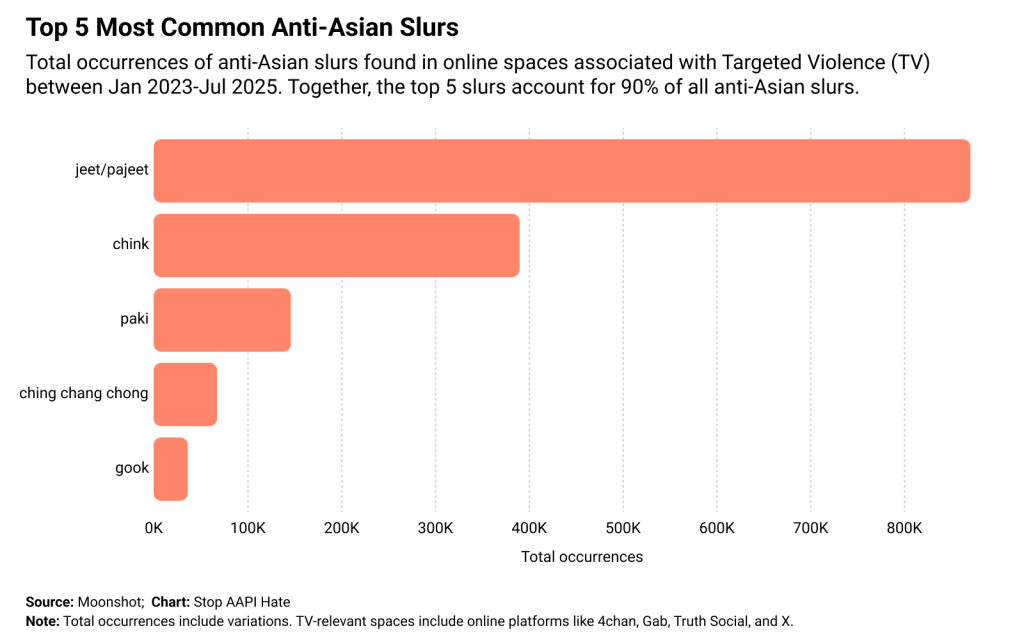

According to Moonshot’s data from online spaces associated with Targeted Violence (TV), the five most common anti-Asian slurs include “jeet/pajeet” (870,821 occurrences); “chink” (390,184 occurrences); “paki” (146,322 occurrences); “ching chang chong” (67,576 occurrences); and “gook” (36,402 occurrences).

Altogether, these five slurs account for 90% of all anti-Asian slurs in these spaces — with the top three alone accounting for 84%.

Why is this important? Because anti-Asian slurs are becoming more and more common in violent extremist corners of the internet. In the past two years alone (from January 2023 through July 2025), there was an increase of 40%.

ABOUT THE DATA

To complete this analysis, we worked with Moonshot, a group that monitors threats of violence and slurs in online spaces associated with Targeted Violence (TV). They define these spaces as “users, groups, and channels that promote violence directed at specific individuals, groups or locations.” – such as popular and niche social media platforms like 4chan, Gab, Truth Social, and X (formerly Twitter).

We paired this data with real-life stories from Stop AAPI Hate’s Reporting Center to uplift and provide unique insights into how anti-Asian slurs are used and experienced on the ground.

1. “Jeet” and “Pajeet”

Most people have never heard the word “jeet” – including many South Asian people — but believe it or not, it’s currently the most common anti-Asian slur in online extremist spaces, and it only started gaining traction in recent years.

So, what is it? “Pajeet” is a made-up Indian name and derogatory slur that originated on 4chan in 2015. Sometimes shortened to “jeet,” it was originally found in alt-right attacks against Hindus and Sikhs, but since entering the mainstream discourse, “jeet” has taken on a broader definition: now, the slur is used to deride not just Hindus and Sikhs but South Asians in general.

➡️ Side note: While “Pajeet” is not a real name, “jeet” is a common suffix in Indian names. Another related slur is “baljeet.” Originally a fictional Indian character who appears on the children’s show Phineas and Ferb, it has also been used as a racial slur. Though the racial slur derives from the fictional character, “Baljeet” is a real Indian name.

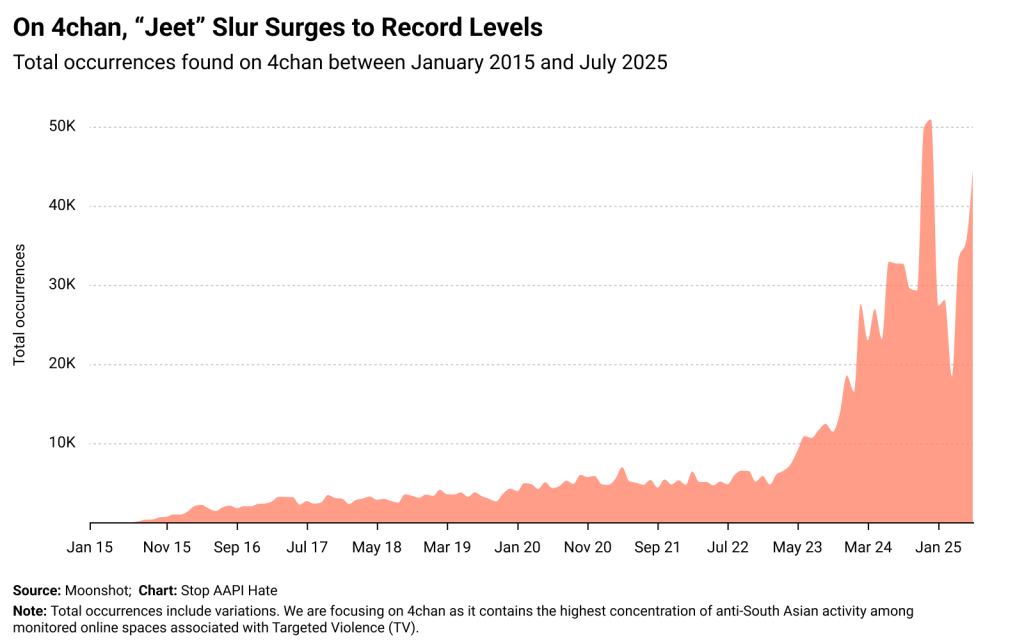

Behind the surge in anti-South Asian slurs like “jeet” is 4chan, where “jeet” and variations of the term were used 44,527 times in July alone. This represents a 33% increase compared to the 12-month baseline, and the third-highest month on record since tracking began in 2015.

➡️ What is fueling the rise of anti-South Asian sentiment online? We break it down for you in this blog post.

Far from the fringes of the internet, “jeet” is also showing signs of entering mainstream discourse in both online and offline contexts. In fact, we are seeing it pop up in reports made to Stop AAPI Hate.

One respondent cited a public X account as “posting abusive and racial content” against Indian people, including the terms “pajeets,” “jeets,” and “cow poop eaters.”

In another report, a parent who attended his son’s high school baseball game reported that his son, along with another Asian player, were taunted with slurs like “P.F. Chang” and “Baljeet.” After speaking out, he was harassed and doxxed online.

2. “Chink” and “Ching Chang Chong”

While “chink” is the second most common anti-Asian slur in our analysis, “ching chang chong”— and variations of the term — are the fourth most common. And unlike “jeet” and “pajeet,” this set of slurs dates back hundreds of years.

Originally aimed at Chinese people, both terms have morphed into catch-all slurs used against anyone perceived as Asian.

In the late 1800s, a wave of Chinese immigrants came to the U.S. to work in gold mines and build railroads. These workers were exploited by employers who underpaid them and were targeted by their colleagues who saw them as a threat. These conditions created a climate of anti-Chinese sentiment that paved the way for the Chinese Exclusion Act as well as racist terms like “chink” and “ching chang chong.”

Back then, people used “ching chong” to mock Chinese people for their language and accent. It even showed up in children’s nursery rhymes.

Centuries later, “ching chong” and the racism behind it are alive and well in the United States. Long before Cierra Ortega and Liam Gallagher, Asian Americans have heard the same slur time and again from political commentators, professional athletes, and countless everyday people.

Take for instance, the mother from Virginia who reported to Stop AAPI Hate after her five-year-old Chinese son was followed home from school by a middle school student shouting “ching chong” at him while filming and laughing.

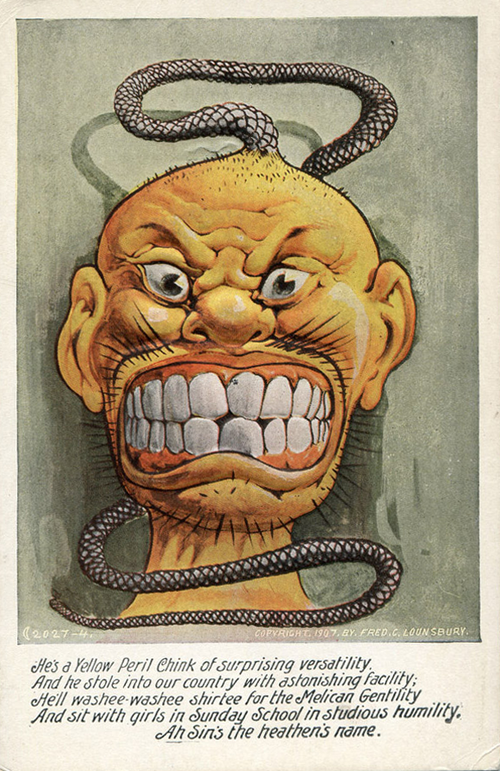

A racist postcard by Fred C. Lounsbury, promoting the idea of the Yellow Peril (1907). Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other reports confirm that slurs like “chink” and “ching chong” are directed at not just Chinese people but at Asian people more generally.

- A Japanese woman in the southern U.S. reported that someone “verbally attacked me and called me a ‘chink b*tch’.”

- A multiracial Filipino student reported his classmates for harassing him in the hallway at school, calling him “ching chong” a “rice man,” and telling him “you don’t belong here.”

- Another case involved a Lao minor who received text messages calling him a “chink” and telling him he was “eating his finest meal” in reference to a photo of him with his dog.

- A Nepalese woman in the midwestern U.S. described walking past a group of teenagers who yelled “ching chang chong” at her.

This kind of broad, indiscriminate targeting is central to many anti-Asian slurs – including “paki” and “gook.”

3. “Paki”

To be clear, “paki” is not a harmless abbreviation of “Pakistani.” It is the third most common anti-Asian slur in online extremist spaces and has long been used to target South Asians and/or people perceived to be South Asian.

The slur originated in England during the 1960s amid a wave of South Asian immigration from countries like Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. Much like “chink” and “ching chong,” this anti-Asian slur gained traction in a political climate fueled by racism and xenophobia, including Enoch Powell’s infamous “Rivers of Blood” speech in 1968 – a moment that legitimized white nationalist rhetoric and turned immigrants into scapegoats. This led to violent attacks on South Asian communities — called “paki-bashing” — that persisted throughout the 1970s and 1980s in England.

By the late 1970s, “paki” had crossed the Atlantic into Canada, where it continues to serve as a blanket slur against South Asian people.

Like other slurs in this list, “paki” hasn’t stayed in one place. It has spread across borders, platforms, and ethnicities, and it continues to fuel hate against South Asian people in England, Canada, and the United States alike. From our reporting center:

“I was talking with my friends and a man came up and started calling me slurs and making racial remarks and stereotyping me as a joke. He called me ‘chink’ because I’m part Chinese. ‘Paki’ and ‘Curry Muncher’ because I’m half Pakistani.”

— Multiethnic Asian woman in U.S.

4. “Gook”

“Gook” is the fifth most common anti-Asian slur in our analysis, though its origins are still debated. Some scholars trace its earliest use to the U.S. occupation of Haiti — where American soldiers used it to describe French- and Creole-speaking Black Haitians and Spanish-speaking Nicaraguans. Others trace it to the Philippine-American War — where “gook” was a derogatory term used to describe Filipinos with no European ancestry.

What’s clear is this: the history of “gook” as a racist slur is also a history of 20th-century U.S. imperialism.

“Gook” has resurfaced repeatedly during moments of occupation, war, and racial violence in Asia — most often as an instrument of dehumanization and a pathetic excuse for acts of government-sanctioned violence abroad. During the Korean War, American soldiers used “gook” to refer to both Korean soldiers and civilians, and during the Vietnam War, it was used against Vietnamese people.

But this term did not end with the U.S. occupation of Vietnam or South Korea. When U.S. soldiers returned home, they brought with them the same racist language and sentiment.

Photo of Umai Bar & Grill vandalized with an anti-Asian slur (2020). Credit: Umai Bar & Grill

In 1988, U.S. actor Mark Wahlberg shouted “gook” and “slant eye” in a violent attack on two Vietnamese immigrants.

In 2000, Senator John McCain invoked the slur on the campaign trail in reference to the prison guards who held him captive during the Vietnam War. “I hate the gooks,” he said, “I will hate them as long as I live.”

But the racist slur “gook” continues to be directed towards Asian Americans of all backgrounds — and not just those of Korean or Vietnamese descent.

From our reporting center:

“[After being featured in an article] someone sent the following message to my business email address: ‘You are a fat, ugly Chink. Get the f*ck out of the U.S. and go back to China, you flat-nosed, slitty-eyed, yellow-skinned gook hoe.’”

— Chinese woman in California

“At the grocery store I was run out of the bathroom. Not only were transphobic and homophobic slurs used but racist and bigoted slurs (‘gook’ and ‘rice picker’) were used as well. I was told to go back to Asia and to perform sexual acts.”

— Filipino/a/x person in U.S.

“I moved into my neighborhood two years ago, and my neighbors constantly call me hateful names (‘gook,’ speak Chinese gibberish when they see me) and destroy my property.”

— Vietnamese man in Texas

Key Takeaways

It’s worth noting that none of the slurs we’ve addressed in this post are outliers. At Stop AAPI Hate, we have seen hundreds of racist dog whistles and slurs against Asian American people — some of them creatures of the internet (like “jeet”) and others a well-established part of U.S. history. But they all have something in common.

All of them have been used by decorated soldiers, movie stars, political leaders, and everyday people, and all have surfaced during periods of heightened racism and xenophobia to reinforce who belongs and who doesn’t.

- Early 20th Century: South Asian immigration sparked fears of a “dusky peril” — described as an even bigger threat than “yellow peril.”

- World War II: At the height of Japanese incarceration, racial slurs like “jap” and “nip” — a shortened version of “Nippon,” the Japanese word for Japan — became common language in media and public discourse.

- Post 9/11: South Asian and Muslim Americans were smeared as “terrorists” and targeted by the U.S. government through the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS) and other racist policies.

- COVID-19 pandemic: President Trump coined “China virus” and “kung flu” to scapegoat Chinese people for spreading the virus, fueling nationwide acts of anti-Asian hate.

The long and short of it is this: Racial slurs are more than just words. Each carries with it a history of violence and discrimination and each has the power to flatten identities, erase cultural differences, and put our families and neighbors in harm’s way.

Naming them is only the first step. The real work is refusing to excuse them, refusing to minimize them, and refusing to let them keep us out of the story of who belongs in America.

Note: This post does not cover anti-Pacific Islander slurs. While these slurs are very real and cause lasting harm to AA/PI communities, they are uncommon in online extremist spaces and we have not received enough reports with anti-Pacific Islander slurs to be able to analyze them.

If you found these data insights helpful, share them with others. If you or someone you know has experienced hate or discrimination, don’t stay silent. Submit your story to our reporting center so we can continue to work towards solutions and raise awareness. And if you’d like a deeper look into our work, check out our latest reports at stopaapihate.org/reports.

Right now, our research and data funding is under attack — to sustain this work, we need your help.

AA/PI communities have long been overlooked and underserved. And to make things worse, the Trump administration just unlawfully terminated two million dollars in critical funding for Stop AAPI Hate, leaving our communities more vulnerable during a time when targeted hate is widespread. With your support, we can continue to conduct research into AA/PI experiences, build resources to keep our communities safe, and support victims of anti-AA/PI hate and violence.

Learn More

Behind the Spike in Anti-South Asian Hate

Anti-South Asian hate is spiking in response to Mamdani’s Mayoral Primary win, debates about H-1B visas, and more.

Report Anti-AA/PI Hate

If you or someone you know has experienced Asian American or Pacific Islander-based hate, we want to hear about it.

Keeping Count | Let’s Talk About Anti-Asian Slurs